Puerto Rico is ready for a revolution. After the leak of an 889-page group chat where Governor Ricardo Rosselló and 11 members of his administration made sexist, homophobic, and racist comments, protestors in and out of the island are asking for the governor’s resignation. It was la gota que colmó la copa. Because in reality, it’s about much more than a leaked chat.

Amidst a decade-long economic crisis and the aftermath of a devastating hurricane, the chat exposed a truth Puerto Ricans were ready to see. The government of Ricardo Rosselló tried to hide stories about the death toll after Hurricane Maria, withheld life-saving aid, made fun of our dead, mocked feminist collectives protesting the femicide crisis, and threatened attacks on journalists, politicians, and celebrities. Furthermore, his administration works to sustain the US-imposed Fiscal Control Board to pay an illegal unaudited debt, which has resulted in hefty budget cuts that have been detrimental to the University of Puerto Rico, healthcare, Social Security and retirement funds. Not to mention, arrests were made to the now former Secretary of Education, Julia Keleher, on accounts of fraud, corruption and money laundering after having closed more than 300 public schools to install a broken charter system on the island.

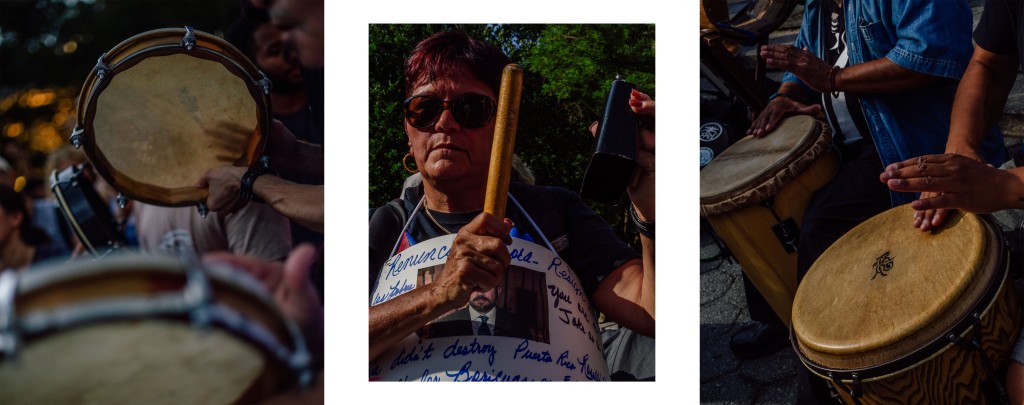

For more than 10 days, Puerto Ricans have taken to the streets to protest in unprecedented numbers. The meanings behind the symbols in these protests reveal the powerful pain, anger, and resilience of the Puerto Rican people.

Their creativity echoes that of worldwide movements, like #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, the LGBTTQIA+ community, and the Women’s March, which have detonated an explosion of political statements on multiple art disciplines. “Perhaps the only good news at a time when so many political issues are hitting home is that we’re now living in an atmosphere vibrating with the possibility of change,” writes Sarah Mower in British Vogue. “It’s a constant ally in times of trouble, a medium open to infinite nuances of meaning in the hands of ingenious people to show their beliefs.”

Be that through a motorcycle cavalry, kayaks, on foot, dancing, with make-up, with musical instruments or the things they wear, Boricuas communicate their indignation to say enough is enough.

Makeup + body paint

Makeup has long been used as a political tool and Puerto Rico’s history is no stranger to such displays. When Lolita Lebrón shot Capitol Hill in 1954, she deliberately wore red lipstick, along with a beret, blazer and long skirt. The politics of this outfit were later immortalized by The Washington Post Magazine’s famous headline about her arrest. It read, “When Terrorism Wore Lipstick.”

Today, in the midst of a historic uprising in Puerto Rico, Lebrón’s lessons live on, as many have turned the red lipstick into large artistic displays of the island’s suffering through body paint.

“I decided to use body paint because art is one of the best ways to express oneself,” Yarelis Pantojas told Emperifollá. “I wanted to show the indignation and fury I feel through more than a poster, but through my body.”

On July 17, when thousands of Puerto Ricans marched through Old San Juan, Yarelis represented the current situation of Puerto Rico on her chest. One half symbolized its angry people, the other the corrupt government. “Wearing that on my body made people understand that this is a protest, not a street party. It’s a fight for our country,” Pantojas told Emperifollá. “My mission was to raise awareness, show our indignation, anger, and pain.”

Makeup and body paint have also been a staple of the social media campaign to raise awareness about Puerto Rico internationally. Those who can’t be present at the protests have used their Instagram accounts to upload their art. From tears in the colors of the Puerto Rican flag to lip paint calling for Rosselló’s resignation, makeup artists in the island have showed their artistry is also a way to fight. Frances Negrón is one of them.

“I’m an extremely creative person and my purpose with my art is that people who have little knowledge of the issues we face today get motivated to learn and fight,” Negrón told Emperifollá. She used black and white to send a clear message: Ricky, renuncia.

While Negrón couldn’t join the mass protests last week, she plans to attend the National Strike on July 22 wearing body paint. “I’m going out to protest and use makeup with a message, posters and t-shirts– all made by me– because I want to show that young people, aside from being creative, we are willing to fight for a better future. That future is ours.”

Dancing Bomba

With its roots in indigenous Borikén’s history against Spanish colonialism, conquest and the trade of African peoples as slaves, la Bomba was born in el cañaveral where enslaved Africans sang, danced and played los barriles as a form of resistance, survival, celebration and healing. Clara Isabel Díaz, a Boricua creative living in NYC, says, “Bomba was prohibited because the colonizers eventually understood that they used it to rebel and communicate feelings in a way that words couldn’t.”

Now, under United States colonialism, the grip of a Fiscal Control Board, and amid worldwide protests for Puerto Rico’s Governor Ricardo Roselló to resign, Clara solidifies exactly how powerful it is to dance bomba. “It is a way of representing our ancestors, a way of saying: ‘We’re here, we matter, and we will continue to prevail even when you want to put us down.’”

Last Wednesday, July 17th, NYC’s Union Square was filled with Boricuas from the diaspora and allies uniting their voices in solidarity and resistance. The sounds of los barriles reverberated among the multitude, and el batey opened in front of us as the crowd sang in unison, Dile, dile, dile, dile a Roselló. Dile a Roselló que mi patria tiene bandera. Of course, Clara was ready with her black scarf, which she used as a substitute to the traditional bomba skirt. “In bomba, each rhythm conveys different emotions or feelings and the words of the songs usually set the mood. That chorus alone gave me goosebumps and was my cue to step into the batey.” Díaz’s scarf was black on purpose because in Puerto Rico, and especially in the context of post-hurricane María, the rise of the black and white flag has become a symbol of mourning and resistance.

“Usually people have colorful bomba skirts and scarves, [which] represents the Caribbean and the cheerfulness of Puerto Ricans, but right now we are not feeling too bright, and so my black scarf is my way of adding to the intensity of the dance and the protests.” Thus, it is no coincidence that this is the only dance where the primo (the principal drummer) follows the dancer, and that it is always front and center in protests. “That day none of the formal aesthetic stuff mattered to me, I was just letting all of my emotions out through the dance. Keeping myself firm in our demands, being surrounded and supported by toda mi gente and hearing the strong drums respond to my dancing was just incredible.”

Bomba has always been a symbol of resistance, and through its practice we not only honor our African heritage and rise against colonial oppression, but together, to the beat of the drum, we (ex)claim, we heal.

Haus of Resistance

The LGBTTQIA+ movement in Puerto Rico is a thing to behold. Even as the government continues to marginalize and ignore cuir bodies, and especially those of black and brown trans women, the community consistently shows up for itself and each other. Thus, in an island where the powers at be dismiss their existence, chosen family is a haven.

On July 17th, after days of consecutive protest in el Viejo San Juan, the legendary Haus of Resistance, born and conceptualized in a group chat, had its first performance. “With bluetooth speakers and three megaphones in tow, the CUIRS organized to throw La Renuncia Ball, held in Plaza de Armas, where we announced our queerness amidst all the protestors and had a fucking BALL!” writes Latinx queerdo producer and performer, gender-fluid drag artist and DJ Kaya Té on their Instagram.

The Haus of Resistance is here to affirm that the community’s right to live happy and healthy lives is not negotiable. Channeling Sylvia Rivera when she witnessed the Stonewall’s Riots, the revolution is here! “It felt more liberating than I had imagined,” Kaya Té tells Emperifollá. “Just the fact that everyone was supporting us, and no one was hating or making us feel uncomfortable was so refreshing. Our intention was to make our presence known. To show and to talk about how our corrupt government is responsible for our marginalization.”

Machismo, homophobia and transphobia is rampant on the island. In terms of gender perspective, there is a lot of work to be done, especially from government officials. But even then, the Haus of Resistance created a space where their performance was the freedom to be themselves, and in response they were met with “a crowd that was willing to listen, learn and celebrate” their lives with them.

The resistance takes many shapes and forms, and we in turn give those meaning. For the LGBTTQIA+ community, it’s their very existence that is perceived as a threat towards the norms and the binary society forces upon us. For Kaya Té, resistance is all about doing everything in your power to take care of yourself and your chosen family. “To listen and fight for the needs of people whose voices are not being heard. Standing up for injustices, no matter how small. Doing everything out of love for yourself and others, and for the strength of your community.”

La lucha será cuir, trans, negra o no será. The Haus of Resistance is here to stay.

Los pañuelos

Borikén has a long history of political resistance. From the indegineous arawak fighting their way through Spanish colonization, they ancestrally set the tone for the continuous fight for our freedom. It’s in our blood. It wasn’t that long ago that political persecution was at its peak, when, from the 1940s to the mid 1980s, more than three thousand nationalists had a carpeta, especially after the 1948 Ley 53, better known as La de la ley mordaza or the Gag Law, which was signed with the purpose of suppressing the independence movement in Puerto Rico. The law made it illegal to display the flag, sing patriotic tunes, or make public expressions that could in any way be interpreted as nationalist. Boricuas were consistently targeted, harassed, persecuted and sometimes even killed for voicing and fighting for Puerto Rico’s independence. The law wasn’t declared unconstitutional until 1957.

Carla Cavina, a Boricua filmmaker and the President of AdocPR (Asociación de Documentalistas de Puerto Rico), spoke to Emperifollá about what it means to use pañuelos to cover your face during protests. “The issue of covering your face during protests is controversial and new to me. I started protesting at the end of the 90s, and back then, it wasn’t a usual practice. It was actually considered suspicious.”

Even in the 50s, with the attack of US Congress lead by Lolita Lebrón, and amid other armed confrontations between nationalists and the colonial insular police, which ended in massacre and hundreds of arrests, covering your face wasn’t a common practice. “The fight was always head on. It was considered a heroic act for la patria,” says Cavina. “When you look at the pictures of protests in those years, it wasn’t something people did.”

However, it wasn’t long before it was discovered that police were infiltrating political groups, pretending they were fellow comrades, which lead to the case of the entrapment and murder of two young independentistas in el Cerro Maravilla in 1978. This shook everyone to their core.

It’s not until the 2000’s that the practice of covering your face with a pañuelo or t-shirt starts to become commonplace. “Maybe it’s because with technology, cellphones and social media, it’s become easier to target and profile people, especially those that protest. Another reason might be that the last few years of violent repression have made our youth rightfully paranoid in the wake of a future that sometimes looks a lot like anarchy.”

“Today’s youth,” says Cavina, “is tired of pacific protests. They want to change the system once and for all. Covering their face serves to tirar la piedra y esconder la mano, so that they can do it again. To light trash cans on fire and graffiti walls.”

On the other hand, police have become fans of using potent tear gases and pepper sprays to corner and demoralize protesters, especially in the last week, where police seem to be throwing gases at midnight like clockwork, illegally claiming the constitution is suspended and thus so is their right to protest. “Today covering your face is an act of defiance. It’s standing up to the harmful gases and the police. A way of fighting against a corrupt government that makes political, economic, social and environmental decisions that undermine the present and future of our people.”

As Cavina noted from the beginning however, this is still a controversial topic. On July 17th in el Viejo San Juan, during the protest convened by artists like Bad Bunny, ILe, Ricky Martin and Residente, Cavina was in the front lines documenting. She had been wearing a painting mask and a bike helmet to protect herself from the gases the police would inevitably throw, if past nights protests were anything to go by. She tells Emperifollá that in the long and tense hours of resistance, she saw a group of masked individuals that insisted on vandalizing and destroying the local news vans.

“My friends and I confronted them in various occasions, telling them not to attack the cars of the people that were trying their best to cover the events and that were clearly demonstrating solidarity with el pueblo’s claims. But their reaction was aggressive in such a way that it made think they were paid to infiltrate. They had their faces covered.”

Today is the historic Paro Nacional starting at 9am on the Expreso Las Américas in Puerto Rico. There will also be several protests in solidarity around the world. Like our ancestors before us, we stand united across oceans, imagining and fighting for a better future for Borikén and our people. Seguimos.

Editor’s note: Frances Solá-Santiago and Maridelis Morales Rosado contributed to this story.

Amazing article 🖤🇵🇷🙏🏻

LikeLike